The key ingredients to a better blockchain, Part IX: Production Readiness

Our understanding of what makes a blockchain successful is becoming clear. What will it take to succeed?

The launch of a new network is the most exciting and rewarding moment in the lifecycle of a project, but it's also one of the trickiest to prepare for. It's good to start preparing early rather than planning a "big bang" launch. (Photo by Hello I'm Nik on Unsplash.)

[This is part of a multi-part series on the key ingredients to a better blockchain. I recommend starting with part one, Tech and Protocol. See the full list of articles in the series.]

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Wallet software

- Regular releases

- Documentation, documentation, documentation

- Identifying and responding to bugs and vulnerabilities

- Bootstrapping mining and security

- Testing

- Multiple client implementations

- Backwards compatibility

- API

- Frontend

- Tooling

- Community channels

- Exchanges

- Governance

- Conclusion

- Notes

Introduction

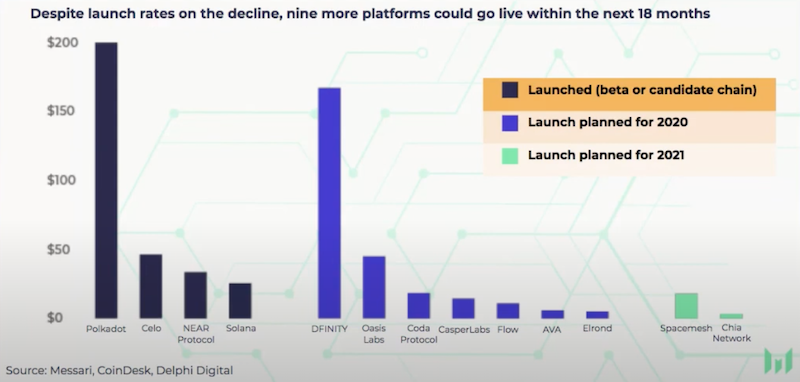

Only a year ago, the idea of a successful mainnet launch was treated more as a joke in the blockchain community than as a reality. The number of projects that successfully launched a mainnet prior to 2020 is exceedingly small, and many projects that had promised to deliver one in 2018 or 2019 repeatedly postponed those launches. By contrast, 2020 has become the long-touted, long-awaited “year of mainnet.” This year has already seen high profile launches such as NEAR Protocol, Polkadot, Celo, Avalanche, Solana, and Filecoin, with others on track for late 2020 and still others for early 2021. Blockchain projects that have made it to mainnet are no longer unicorns.

Image source: Messari

Image source: Messari

The most critical juncture for any project is the transition from an initial, focused R&D phase to a production launch. It’s truly a phase shift: the processes that serve a project and a community well during the R&D phase are probably not the ones that will be needed to address issues that arise in production.

In the early days of a project, policies and procedures can be fairly loose. There is very little at stake and the community is small and focused. The team knows and trusts each other. Things are relatively centralized within a single company or organization. Don’t take for granted how easy it is to coordinate work during this phase, and how much harder things get when there’s a larger and more diverse group of stakeholders, and when there is more at stake! Protocol changes become harder over time.

This article discusses steps that project teams and communities must take to successfully complete the critical transition to mainnet, and to prepare for what comes after. Note that, while most of these best practices apply to any mature, production grade software, they’re especially important in the blockchain space due to its adversarial nature and what’s at stake economically.

Wallet software

A great place to start preparing for mainnet is with well-designed wallet software. While testnet tokens have no real value, this is obviously not the case on mainnet. It’s not a disaster if a user loses access to a testnet wallet, but the consequences are much greater if those tokens have value. Production-grade wallet software should make it very easy to generate, back up, and restore credentials and keypairs for multiple accounts.

While software wallets are a prerequisite for production readiness, they’re not sufficient. In addition to basic wallet software, a network should also support hardware wallets and multisignature wallets (a.k.a., multisig), both industry standards. Note that hardware wallet support is much easier if your network uses a standard signature scheme that’s already supported by common devices from vendors such as Ledger and Trezor.

Since multisig is the gold standard for securely storing cryptographic assets, sophisticated investors won’t invest much in a network without robust multisig support that’s both secure and easy to use. These design requirements are common and well understood. It should be straightforward for any network with basic smart contract support to implement a multisig. Even Bitcoin, with only a barebones scripting language, has native support for multisig wallets.

Regular releases

The release process tends to be haphazard early in the life of a project. Multiple developers may cut ad hoc releases from time to time to fix bugs, address issues, or add features. Releases may not have proper versioning. As with any mature software, this process should get much tighter and more disciplined before a production launch. There should be a single release manager who owns the release roadmap and is responsible for cutting all releases. This release manager is responsible for deciding what to include in each release, working with R&D to make sure release targets are met, making sure tests are run, writing release notes, coordinating versioning and releases of related infrastructure and applications, notifying interested parties, etc..

Releases should happen regularly. Precisely how often is a subject of some debate, but the “Goldilocks spot” is a frequency that’s high enough to address major bugs and issues as they arise, but not so high that it creates an undue burden on node operators. Releases should be frequent in the beginning, but should probably become less frequent over time as the software and protocol mature and stabilize.

More important than frequency is predictability. There should be transparency into what’s slated for inclusion into upcoming upgrades and when those upgrades will happen. This should be integrated into a support system, so that users know their issues are being addressed, and which release will include a fix for a given issue. The build process should be well documented and verifiable so that developers can easily build and verify the software themselves on multiple platforms. If you correctly use a mature continuous integration system such as GitHub Actions, cutting a release should be as simple as creating a tag on your main branch and adding release notes.

Note that there is a big difference between a routine upgrade and a protocol upgrade that requires a network hard fork. While the former should be relatively frequent, the latter should be infrequent due to the coordination effort that it entails. More on this below.

Documentation, documentation, documentation

As discussed elsewhere in this series, documentation is as essential to production readiness as it is to usability and community. Users rely on documentation to understand how to download and run your software, how to generate and use wallets and accounts, and how to submit transactions. Miners, exchanges, and other node operators rely on documentation to set up tooling and devops and securely and safely run production-grade nodes. Developers rely on documentation to get started building applications and contributing to infrastructure. It’s expensive to build and maintain good documentation, but as it’s valuable to so many parts of the community, it’s clearly worth the cost to develop and maintain great documentation.

Identifying and responding to bugs and vulnerabilities

While bugs are expected in a testnet, the situation in a production mainnet is another story entirely. A great deal of value and user data is at stake on a mainnet. It’s essential that proper policies, procedures, and disclosure frameworks be established for mainnet security incidents prior to a production launch. This is not as straightforward as it seems. There is often a difficult tradeoff between on the one hand maximizing transparency and reporting issues as soon as possible, and on the other hand addressing critical bugs before they’re exploited in the wild. For a recent example of how hard it is to get this right in a production network, see the Geth v1.9.17 Post Mortem which explains how a bug that was quietly fixed in a more recent version of go-ethereum caused a consensus issue when some node operators didn’t upgrade. See also cases from Monero, Zcash, and Bitcoin.

While they cannot prevent all issues, third party audits are a great way to spot possible issues before they escalate into real vulnerabilities in production. There are a number of experienced teams of auditors that have worked with multiple blockchain platforms and are familiar with the risks and challenges associated with blockchain platforms and software. These professionals have studied more blockchain software and infrastructure and identified more issues than any individual team is likely to be able to. Audits are good at spotting high level architectural issues, and less good at spotting tiny bugs—but they’re absolutely essential for any production-grade blockchain platform. Wise, experienced users and investors won’t put much trust or value into a system that has not been audited once or, ideally, multiple times by multiple teams of auditors.

Bounties can also increase trust in a similar fashion, especially if they’re large enough and have gone unclaimed for a while. At the minimum, mature projects establish bug bounties (to incentivize security researchers to report vulnerabilities rather than take advantage of them or sell them to those who would), a channel to anonymously communicate security issues and fixes, and a vulnerability disclosure policy.

Bootstrapping mining and security

All blockchain networks need a minimum number of miners or validators to participate in the consensus process and keep the network secure. If there are too few, adversaries can attack the consensus process through, e.g., a 51% attack, and the miners can be attacked directly through DoS attacks, eclipse attacks and the like. Too few miners also make a network less censorship resistant.

Over the long term, a platform with good incentive design should have no problem attracting a sustainable community of miners. However, even the best designed networks face a bootstrapping problem: if the network isn’t secure enough at launch, few will use it. And if few use the network, it won’t be secure enough.

In the case of successful networks like Bitcoin and Ethereum, network effects have led to a virtuous cycle of increasing network security and value. New networks need to find a way to bootstrap this cycle and recruit a minimum number of miners at launch. Recent, successful network launches have featured contests, games, hackathons, prizes, bounties, etc., all of which can help, although if poorly executed they run the risk of appearing gimmicky or attracting short-term profit-seekers rather than those invested in the long-term health of the network.

As a project team, it may be possible to run a sufficient number of miners to bootstrap a network launch on your own. You should figure out the minimum viable security level that will be required at network launch, how to recruit that many nodes, and how much it would cost to augment them with your own managed nodes. However, attempting to run all of the nodes yourself on a single cloud provider is a bad idea since it increases the chance of network failure and thus fragility. Also note that recruiting miners is not that different from recruiting other classes of stakeholders such as developers and investors. It requires many of the other tasks discussed in this and the other articles in this series: good documentation, support channels, software that’s easy to run and maintain, etc.. If you’re already following other best practices it shouldn’t be that much more work to recruit a healthy community of miners.

Testing

Given the highly complex nature of blockchain software and the potential for harm if the software fails, it’s essential that blockchain project teams employ software engineering best practices including testing. This should include basic unit tests as well as black box/application/integration tests and regression tests. Test-driven development is a great way to instill a culture of always writing tests and making sure that testing doesn’t fall behind in order to meet deadlines.

All well-engineered, production-grade software should ship with a robust suite of unit tests. A blockchain full node is no exception. The code should have a thorough test suite that provides a high degree of coverage over all of the various features and components of the system. As one example, Ethereum has a comprehensive suite of around 40,000 individual tests that all full node implementations are expected to pass. This suite is further broken down into many different classes of tests which are each responsible for testing a different part of the system: the blockchain, the VM, transactions, the network layer, etc..

One further note on testing: blockchain is unlike most other software, even other complex, networked systems, because of its decentralized, peer-to-peer topology. Due to changing economic and network conditions, the number of nodes participating in consensus at any given time can change quite rapidly and this can have a serious impact on the system. These scenarios are notoriously hard to test, and while no test can perfectly replicate real-world scenarios, the dual strategies of simulation and emulation can get you 80% of the way there.

Simulation involves building models of realistic economic and network conditions and running them through various stress tests to see how the platform responds. Because a live blockchain network has many classes of users with different incentives, multi-agent modeling is a good starting point for a simulation. Emulation involves tests that get even closer to reality: whereas a simulation typically runs on a single system, emulation might involving firing up hundreds or even thousands of nodes spread out on different subnets and network infrastructures, operating systems, and architectures, around the world. It’s essential to run tests that escape lab conditions and get as close to real-world scenarios as possible. This level of sophistication in testing is beyond the means of many project teams, but there are professional teams with heaps of experience that can help devise a strategy, build the infrastructure, run tests, and analyze the results.

Multiple client implementations

As discussed previously in this series, the question of whether and to what extent it’s desirable to have multiple client implementations to run a blockchain network is somewhat contentious. However, without multiple implementations, ideally written in different languages and frameworks, supported and maintained by different teams and organizations, you cannot realistically refer to the thing they implement as a protocol.

It’s useful to have multiple implementations for a host of reasons. For one, they allow more customizability, as different implementations likely excel at different things.1 For another, they act as a powerful decentralizing force in governance. And perhaps most importantly, they help in the detection of critical bugs and help the network withstand attacks.

While a single, complete, well-tested implementation is sufficient to run a testnet and launch a mainnet, you should begin thinking early about how you might incentivize multiple implementations to be built by the time mainnet launches. You might build a second implementation in house, outsource it to an experienced team of developers, or leave it as a task for the community, incentivized by grants and bounties.

Note that having multiple implementations also necessitates having a formal protocol specification that multiple teams of developers can build and test against, and contribute to. It’s good practice for this reason alone, and implementing the same protocol multiple times in multiple languages using multiple architectures and frameworks is an excellent way to battle test a protocol design. Having a formal specification makes testing and auditing easier, and also helps ensure backwards compatibility in the protocol.

Backwards compatibility

Breaking changes can and should happen often early in the network and protocol lifecycle. They should become accordingly less frequent as the software, protocol, and network evolve. While regular software updates—which fix bugs and add new features—should be common, protocol changes should be rare. When they do occur, it’s essential that they only add functionality and not break existing functionality. The only exception to this rule should be a security issue that requires a breaking protocol change to address.2

The reality of a protocol and a software platform (as opposed to a simple application) is that there are many downstream users, applications, and products that rely on it. In the case of blockchain, that may include a long value chain and a lot of value. As a result, changing a protocol should be less like changing a line of code and more like changing a law, a treaty, or a constitution (see more on governance, below). There is, in essence, a social contract, explicit or implicit, that exists between the core developers of a platform or protocol and the downstream developers, that breaking changes will not occur. It can help to make this contract explicit so that developers that rely on the platform know what to expect and can be sure that their applications will be able to run for a long time.

My visualization of a bug that ends up getting incorporated into a protocol. (source)

Here as elsewhere, it’s worth pointing out that this challenge is not unique to blockchains. All software platforms deal with the challenges of having an installed user base, and as a result long-lived platforms have ample quirks and oddities that will be part of them forever (see, for example, the history of x86, quirks mode on the Web, and One JavaScript for examples from other platforms). Even bugs in the original protocol have a tendency to become canonical once they’ve been released into the wild!3

While some platforms have been more aggressive about forcing upgrades and breaking changes (e.g., Python and Apple), this challenge is even more severe for blockchain than for other types of applications, given the permanent nature of blockchain data and applications. A smart contract deployed on Ethereum or a similar platform should be able to operate for 100 years with no ongoing maintenance, at least in theory.

There are certain clever ways around this problem, such as emulators, but they are not mature nor well-tested. There is a plan to merge the existing Ethereum network and the new Ethereum 2 network after its successful launch. One proposal for how to do so is to “collapse” the existing Ethereum blockchain down into a smart contract or a shard that will continue to run indefinitely inside a new Ethereum 2.

API

The importance of a good API in a blockchain client cannot be overstated. Like most systems, a blockchain node is invisible by default: it runs in the background, exchanging data, participating in consensus, and managng a database. In order to know what’s going on, and to be able to interact with the running node—in other words, to do anything useful with it—applications have to communicate with a node using its API. The API allows the user to view the P2P network status and synchronization progress, to start or stop mining, to query accounts, balances, and transaction status, to view and update configuration options, and to submit new transactions.

The most common protocol used in blockchain node APIs is JSON-RPC, which is not the most intuitive nor the simplest, but it has the benefit of using HTTP so client software such as wallets and Javascript-based Web3 applications can easily talk to it. Some modern clients choose to use GRPC instead, which allows client code to be auto-generated for a variety of different languages. GRPC is well documented and under active development by Google. It also gives you a RESTful JSON API for free so it’s the best of both worlds.

As with all of its other features, it’s important that a blockchain’s API be well documented to improve the experience of developing applications.

Frontend

Most of the early design and engineering effort in blockchain tends to go into the backend, including components like database, consensus, and P2P. This is understandable since those are the trickiest, most complex parts of the infrastructure. However, it’s important to keep in mind that a product approach to a blockchain means more than an invisible backend. Even with a well-designed API in place, it’s simply not practical for most users to interact with a node using text-based commands and curl. In order for a blockchain to feel like a tangible product to developers and end users alike, it needs a frontend. The frontend of a blockchain usually takes the form of a suite of applications including wallet, block explorer, and dashboard, which communicate with the node using the API.

As discussed elsewhere in this series, a wallet application allows the user to manage one or more accounts, to see their balance and incoming and outgoing transactions (as well as rewards received, in the case of mining), and to send transactions. Some wallets also allow interaction with layer two applications (dapps). The block explorer provides a more objective view of the network: it shows all transaction and block data in real time, and allows the user to track the status of any transaction or view any account’s balance. (For good examples of production block explorers, see Blockchair, Polkascan, and Etherscan.)

A third common application, nice to have but a little bit less essential than wallet and explorer, is the dashboard. Whereas a block explorer displays data on historical blocks and transactions, a dashboard allows the user to see the status of one or more running nodes: its sync status, how long it’s been running, its latency to the rest of the network, its number of peer connections, the version of the client software it’s running, etc. (For good examples of production dashboards, see Ethstats, Big Dipper, and Polkadot staking.)

As with a second client implementation, there are many ways to develop a frontend: in house, outsourcing, or leaving it up to the community of open source developers.

Tooling

As discussed previously in Usability, good tooling can make all the difference for both developers and users. Users rely on tools such as block explorers and wallet/key management software. Developers rely on tools for building, testing, deploying, and maintaining smart contracts, running and monitoring node software, communicating with a running node, and testing and interacting with the API. They also rely on frameworks and SDKs that facilitate reading data and submitting transactions for building higher level applications. The better and more mature the tooling, the better the UX and developer experience it enables and the easier it is to build mature, usable applications on top of the blockchain. A blockchain that makes it very difficult to develop usable applications is not one that’s ready for production! For all of these reasons, tooling should not be an afterthought and its design and development should be prioritized alongside node software, frontend, and API.

Community channels

Early in the life of a platform, most or all communication will happen internally among the core team. Over time, however, a healthy project will naturally attract a broad community of enthusiasts, developers, investors, miners, and other stakeholders and contributors. These community members will need a place to congregate, find one another, and share ideas. In particular, they’ll need a place to ask questions and find answers.

The goal of a blockchain project should be to migrate away from centralized tools, and to dogfood Web3 and decentralized applications as much as possible. While platforms and protocols like Matrix and Status have come a long way, the reality is that most Web3 applications still aren’t very mature and tend to be difficult to use and unreliable. We should keep an eye on these tools and use them whenever possible. However, communication and coordination are extremely important and, while some may disagree, I encourage project teams to use well designed, centralized platforms as a stopgap until the Web3 ecosytem is more mature.

While Slack is intended for use among a trusted group, e.g., an internal company or project team, and thus has very limited moderation and community management capabilities, Discord in particular has proven itself very well-suited to managing communities. It has sophisticated support for different classes of users and permissions out of the box, and can easily be extended with various customizations, integrations, and bots. To support this use case, Discord has introduced new community server features recently.

Other channels such as Twitter, Reddit, and Telegram are also popular among blockchain communities. Each has its strengths and drawbacks and each is popular among a different audience. It’s important to understand each of the constituencies within the community and their needs and preferences, and to recognize that a single channel or app may not suit all of them. Developers and investors tend to hang out in different places and to prefer different communication styles. Some particularly active subgroups, such as miners/stakers/validators, may prefer a separate community focused exclusively on the topics that interest them.

While it may therefore make sense to have a presence on several such channels, be mindful of opening lots of social media accounts or hosting chat servers if you don’t have the resources to maintain and engage with all of them! Other things being equal, avoiding a platform or channel is generally better than engaging with it halfheartedly.

Understanding and managing a community is not easy. For any sizeable community it’s truly a full-time task, and for teams that have the resources, hiring an experienced community manager who can focus on this task is a great idea. You may also be able to recruit community moderators from among active groups on a per-group basis. See the Stack Exchange moderator system for inspiration on what’s possible when this is done well.

Exchanges

Once you’ve launched a stable mainnet it’s highly likely that your native token will be listed on one or more exchanges. While many teams and communities would prefer to delay listing as long as possible to prevent the sort of rampant speculation that has given the blockchain space a bad reputation, in a permissionless network there is of course nothing that you can do to prevent it. You can, however, prepare for it in several important ways.

The first and most obvious way is economics: avoid having too large a premine or issuing too many tokens early in the life of the network. You can and should also impose vesting on early investors and team members, enforced in software, so that no one can “dump” tokens on the market.

Nextly, you should have legal counsel, a legal stance, and a plan of action. Is your token a security, or not? In which jurisdictions might it be classified as such, and why? In order to answer questions such as these, or to engage fruitfully with legal counsel to find answers, it will be necessary to think carefully and honestly through the questions presented in Economics. What role does/do the token or tokens play in your network? How does one earn tokens, and what can they be redeemed for?

Note that it’s not practically possible not to have a stance on these questions. Refusing to engage with them or attempt to answer them does not protect you from, e.g, an SEC enforcement action. It may be possible to assert that a network is decentralized and thus in the hands of its users rather than in the hands of one organization as there is precedent for this, but the burden of proof has become greater recently.

There is also a technical component to tokens listing on exchanges. Exchanges will need to run their own nodes, and may therefore become one of the more important infrastructure providers on the network. To the extent that you feel comfortable engaging with exchanges and supporting their work, you should be prepared to offer high touch technical support, especially in the beginning, to make sure that they’re able to successfully run and integrate with your software and participate in network upgrades and governance.

It’s worth noting that historically some exchanges, especially the more popular ones, have asked projects to pay “listing fees” that may be as high as a million dollars. You should consider for yourself the legality and ethicality of paying such fees, as well as how much it’s worth to list your token on a particular exchange at a particular time. Rest assured that any successful project will eventually be listed on major exchanges since it’s in their interest to do so, regardless of listing fees.

Also bear in mind that different jurisdictions have different rules regarding trading of cryptographic assets, and rather than attempt to comply with burdensome regulations, many exchanges simply block users from such jurisdictions from accessing their platform entirely or from trading certain assets. Many major exchanges block all customers from the United States, and residents of New York face even more onerous restrictions. For this reason, some or many of your project’s stakeholders may face severe obstacles to acquiring and trading your token even once it’s listed—all the more reason you should reward various forms of meaningful contribution to the project and community with tokens wherever possible! Fortunately, the rising popularity of mature decentralized exchanges such as Uniswap, and the depth of the markets they host, mean that the importance of highly regulated centralized exchanges will decrease over time. Listing a token on a decentralized exchange currently requires bridging it to Ethereum and that platform’s robust DeFi ecosystem.

Governance

As discussed above, in the early days, changing the software or even the protocol itself is typically a decision that’s in the hands of a small number of core developers. During the R&D phase, a single developer might change the protocol unilaterally by changing a single line of code. The change may be discussed in a team meeting or on a GitHub issue. During the subsequent testnet phase, protocol changes are less common. There should be fewer changes, they should emerge from team consensus, and they should be infrequent. They can only be rolled out when the testnet is relaunched, which should not happen too often.

As a project transitions into production, however, making changes naturally becomes more burdensome. This is by design since a production network has a much larger set of stakeholders and an installed user base, and any changes post-genesis should take into consideration the concerns of active stakeholders (if not potential, future stakeholders as well). Protocol changes should become increasingly infrequent. They’re unlikely to be rolled out more than once or twice a year, and they almost definitely need to be backwards compatible.4 As the frequency of protocol changes decreases and the corresponding difficulty of making changes increases, the cost of mistakes and bad design and engineering decisions increases because the protocol will likely be stuck with them forever.

The process of understanding the needs of diverse stakeholders and negotiating whether, when, and how to include them in the release, update, and maintenance process is called governance. Governance becomes necessary the moment a network goes live in production, and while it’s less critical prior to this point, there’s lots of groundwork that can be laid early on. It’s a good idea to start early because governance only becomes more difficult over time as the number and diversity of stakeholders and the amount at stake grows.

Some basic principles of good governance are clear delineation of roles, responsibilities, and accountability processes so that stakeholders can see clearly how decisions are being made and know whom to hold accountable for those decisions. Additionally, changes should be communicated well ahead of time, and stakeholders should know how to weigh in and participate in the decision-making process. Records of the process, such as recordings of calls or chat transcripts, should be made available indefinitely to the public, or at least to network stakeholders. This is true for technical as well as for non-technical changes, such as those that impact economics. All stakeholders should be aware of various economic policies that may impact them, how and when those policies may change, and how they can communicate their needs, propose ideas, and participate in the decision-making process.

As discussed above, it’s important that there be clear, official, established channels for communicating about and coordinating upgrades, bugfixes, and responses to security incidents. This may involve roles such as core developers, security officers, community/communication managers, a technical steering committee responsible for setting the overall roadmap, and representatives of essential constituencies such as miners, validators, exchanges, and node operators. All of this takes time to design, build, and launch, so you should begin the process early to be ready in time for mainnet.

Lastly, the value of a clear roadmap and strong leadership cannot be overstated. One of the greatest risks of decentralization is a lack of strong leadership. This can lead to a lack of direction, like a row boat where everyone is working hard but rowing in different directions. Early in the project lifecycle, up to and including the launch of a mainnet, and before the project achieves stability and maturity, strong, centralized leadership can be helpful. It simplifies communication and coordination and allows the team to respond quickly when things go wrong. Over time, as a platform and community mature, it makes sense to give more agency and authority to the community and to remove the core team as a single point of failure.

Note that strong leadership does not necessarily imply a single leader! The best projects tend to have leadership that’s multipolar, but that is nevertheless able to coordinate and act in concert, in the best interest of the network at large. Having multiple poles of governance, power, and influence, and multiple strong, trusted leaders means that these leaders tend to keep one another honest and in check, and make up for one another’s failings and oversights. Good leadership structures take time to develop but there is much that can be done to facilitate this development, such as making room for many voices in platform development and governance.

For more on this topic, see Governance.

Conclusion

As I hope this article makes clear, the transition from the R&D phase to the production, mainnet phase is the most important in the life of any project, including a blockchain. It’s one of the most exciting moments, but it’s also one of the most dangerous. The production phase requires a very different set of actions, a very different sort of communication and coordination, and a very different approach to the platform and product than any prior phase in the lifecycle. In some cases, the team that successfully designed and built the platform may not be the right team to operate it in production, and to navigate the intricacies of community and governance. It’s essential that blockchain product teams be honest with themselves about their strengths and weaknesses, and recruit team members and allies with the right set of skills and experiences to maximize the chance of the long term success of the platform.

However, for the project team, finally seeing the thing they’ve worked hard to build come to life and mature into something that more and more people use and rely on is an incredibly rewarding experience. Congratulations on making it this far in your blockchain product journey :) Few teams and projects do!

The final section in this series, Sustainability, will discuss a few ways to keep a project, platform, and community healthy and active far beyond this initial production launch phase.

Notes

This article is part of a multi-part series on the key ingredients to a better blockchain. Check out the other articles in the series:

- Part I: Tech and protocol

- Part II: Decentralization

- Part III: Community

- Part IV: Constitution

- Part V: Governance

- Part VI: Privacy

- Part VII: Economics

- Part VIII: Usability

- Part IX: Production Readiness

- Part X: Sustainability

-

Different classes of users use node software for different purposes and thus have different requirements. For instance, an exchange may need to manage only a small number of wallets but need to support massively parallel transaction processing. A firm doing analytics may not need transaction processing at all, or may not need data that’s immediately up to date, but will likely need a database that’s tuned for reading huge amounts of data, possibly in parallel. A core R&D team may not care about the database, but may want node architecture that’s flexible, modular, and extensible. In order to support as many use cases as possible, node software should not be monolithic. ↩

-

One such example of a critical fix to a live network that necessitated changing the protocol was the Ethereum network upgrade that occurred in October 2016 in response to a DoS attack. ↩

-

When I say forever, I really mean forever. Bitcoin and Ethereum have both incorporated bugs into their respective protocols because the cost of doing so was less than the cost of fixing them. This phenomenon is called bug compatibility or, affectionately, “bugwards compatibility.” This might not be such a bad thing. ↩

-

Of course, different projects handle their release schedule differently. Some occur frequently, some occur infrequently, and some are more liberal with protocol changes than others. But the point remains: a given network in production releases fewer, less frequent updates than the same network in the R&D and testnet phases. ↩