Software and the IKEA Effect

The more we invest in the software we run, the more we value it. As users and as developers, let's make sure we're investing in the right things.

If you've spent as many hours assembling IKEA furniture as I have, this photo should trigger you. Don't worry, we'll do better with software. (Photo by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash)

A few days ago I set up an Eth2 validator to participate in the Eth2 beacon chain genesis event. This required reading several pages of documentation, making the necessary Ethereum transactions, backing up the credentials, allocating hard drive space and setting up a VM, downloading, configuring, and running the node software, syncing the node, then double and triple-checking everything to make sure I hadn’t made any mistakes. The whole process took a few hours, and at the end, I had a running validator. In the days since, I’ve spent several additional hours monitoring it and troubleshooting. So far, I’ve earned around $15 worth of ETH, and the APY on my initial investment is estimated to be around 3%. Even the ETH I’ve earned lives on the new beacon chain, not the Ethereum mainnet, so I couldn’t withdraw or spend it even if I wanted to. That means, strictly speaking, I should discount this yield to factor in opportunity cost and risk. Why work so hard for so little reward?

It’s definitely not about the money.

For one thing, the process of reading, transacting, downloading, configuring, and running the node is educational and the experience is valuable. Designing incentives and writing code are one thing, but actually participating in a real, live, running network, with real funds on the line and real skin in the game, is where the rubber of blockchain meets the road, so to speak. Lots of things you don’t expect and cannot predict happen when you participate in a live, production network.1 As someone who builds blockchain software for a living, it’s important for me to have experience participating in as many networks as possible.

For another, there’s the community. While I haven’t personally been involved in the development of Eth2, many of the people behind it are friends. I want a chance to understand and support their work, and joining the network is a great way to do that. I want to see the network succeed.

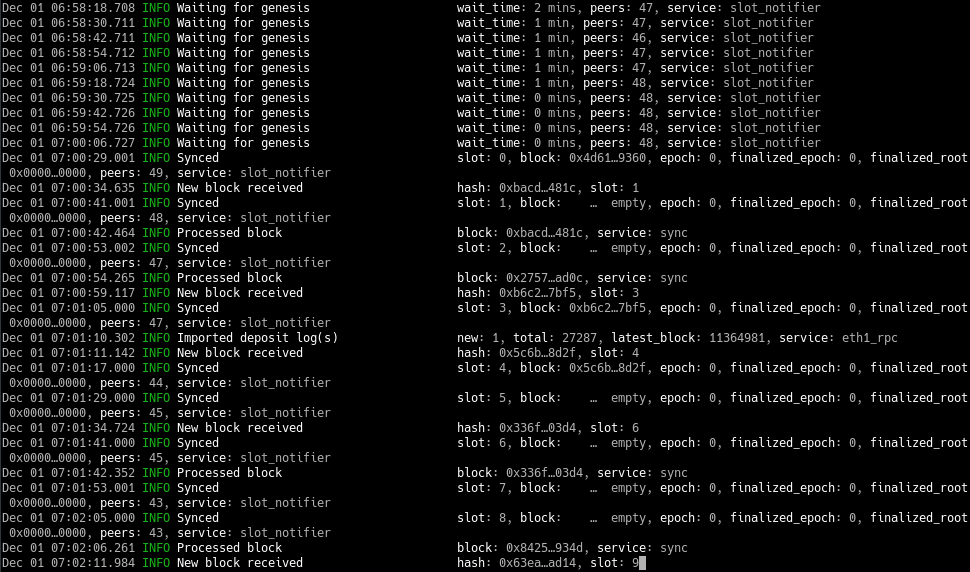

Watching the Eth2 Beacon Chain genesis on December 1

Watching the Eth2 Beacon Chain genesis on December 1

Finally, there’s the joy and satisfaction of successfully setting up something complex and seeing it come to life. When the setup process was done, genesis happened, and I saw my validator begin successfully posting attestations, it was an exciting feeling—even in spite of the fact that I can’t currently use the network to do anything else! Having joined the community in 2017, I missed the genesis event of the original Ethereum network, so participating in the Eth2 genesis gave me a taste of what it must have felt like the first time around. There is some magic in seeing a piece of software, a network, suddenly spring to life when you’ve been following it for a long time and feel invested in its success, especially when you’re contributing meaningfully to the launch by running a node.

I certainly never felt that way about a macOS update or a Slack upgrade, which goes to show the power of open networks that allow anyone, anywhere to contribute and participate in design, engineering, operation, and governance.

The experience made me realize that there’s an interesting tension in designing and building software. On the one hand, application developers want their apps to be as easy as possible to install and run so that as many people as possible are able to use those apps, and choose to do so often. Application developers and publishers have decided to take away agency from the user, unilaterally and paternalistically removing all of the rough edges from the experience in order to cater to the lowest common denominator, i.e., the least savvy user. Far from being able to customize the apps we use, we no longer control our credentials (Facebook and Google do), we no longer control where and how applications are installed, run, and updated (they live on the Web, not on our devices), and we no longer control what content we consume (algorithms predict which content will be most engaging and social media applications push this content to us). Increasingly, we don’t even control our own data: files that live on our devices are rapidly being replaced by amorphous blobs of data that instead live inside proprietary databases that we have only narrow, mediated access to. All of this makes signing up for and using apps quick and easy, but it deprives us of nearly any agency in the process.

At the same time, however, developers want us to invest time and energy into their apps to make them more “sticky.” This increases switching costs, reducing the likelihood that a user will switch to a competing app or platform, especially if you don’t allow users to easily export their data. It also leads to a phenomenon known as the IKEA Effect: people tend to value things that they invested time and energy in (“some assembly required”) more highly than things that don’t require this investment. Entrepreneurs have long been aware of and exploited this phenomenon, especially in software.

The result of this tension is applications that allow (and in some cases require) the user to invest time and energy but only in very superficial ways. These apps are designed to give the user a semblance of control and agency while in fact ensuring that all real control remains squarely in the hands of the app’s publisher. While the public has begun to wake up to the dangerous realities of surveillance capitalism, the attention economy, and highly targeted content, the situation is in fact even worse than most people realize: we’re being manipulated by the software we use, the content we read, and the networks we participate in for the benefit of the corporations behind them, but we’ve been fooled into thinking we’re actually in control.

This manipulation tends to be subtle and feel relatively benign. It includes behaviors such as customizing our profile or an app’s layout or colors, adding widgets, following suggested friends or influencers, collecting “karma” or reputation points, signing up for loyalty programs and collecting rewards, and customizing game characters with unique weapons, outfits, and abilities. More perniciously, it also includes apps siphoning up our most personal data, often with the excuse of backing it up or making it easier to share: migrating all of our documents to Google Docs, or sharing access to the contacts and photos on our devices with apps that move this data “to the cloud” (i.e., onto private databases on a company’s servers). Sometimes it can even be downright hostile, a phenomenon known as dark patterns: e.g., causing you sign up for something or purchase something you didn’t intend to, or making it impossible to close an application or website. Of course, these applications never give the user real control over the things that actually matter, such as the application’s data and algorithms.

All of this was maybe, just maybe, understandable at the beginning of the mass migration into the digital age, when most users were unsophisticated and undemanding: digital “tourists” rather than digital “natives.” Tourists are okay with bland hotel rooms that they can’t customize because they know they’ll only be there for a few days. But we’re spending more and more of our lives inside digital spaces. It’s only natural that we become tired of the bland, one-size-fits-all appointment of these spaces and, over time, desire to customize them to suit our tastes and preferences. I think the IKEA Effect may hold the key to achieving this.

As users, we should be aware of how the software we use manipulates us—through dopamine hooks, triggers, and notifications, but also by coercing us into handing our data to companies and investing time and energy in platforms we have no control over. We should pay particular attention to what the apps we use and the digital spaces we inhabit allow us to control, and what they do not. We should demand that these apps and platforms give us agency and the ability to customize our experience, and our spaces. We should demand that they make it easy for us to leave when they fail to do so—and we should leave the ones that don’t, choosing to invest our scarce time, energy, and attention elsewhere. Finally, we should demand that these platforms also provide us a way to benefit economically from our attention, participation, and contributions.

As creators, we should design and develop software that takes advantage of the IKEA Effect, not in pernicious or superficial ways but in deeper, more meaningful and constructive ways. We have excellent examples of how to do this in the many successful P2P and open source projects, where anyone can contribute, anyone can have a say in the decision-making process, and anyone can participate in the network as a full peer. We should think about the wider ecosystem where our software lives and about the digital spaces it enables. We should continue to look for ways to include the user, deeply and meaningfully, in the value creation and distribution process.

This model won’t work equally well for all software and all users. I don’t expect participatory software such as blockchain, Web3, and P2P to take over the world overnight. While the experience will no doubt get better over time, today these tools are still tricky to set up and use (as my experience setting up an Eth2 validator shows). Even the most sophisticated, demanding users don’t want to have to spend hours configuring every application they use. Helping build and operate open software and networks requires a huge commitment of time and energy. I want 80% of the software I use to work “out of the box” with little or no fuss or customization required.

But the other 20%, the apps, tools, and spaces where I spend 80% of my time and energy, are another story entirely. I want to have agency and a meaningful degree of control over these. It will be a long, messy process, but over time more users will demand more control over more tools, and over time, we will gain that ability. Forward thinking application designers and developers see the writing on the wall.

It’s important to note that the IKEA Effect is not only beneficial to consumers: it’s good for producers, as well. IKEA didn’t start out asking consumers to assemble their own furniture as a way to make them feel better, of course: it was a way to save money and reduce prices. The same thing is true of software. We’re entering an era where software developed by scrappy, global teams of motivated hobbyists, empowered by better collaboration tools like GitHub and StackOverflow, is starting to be competitive with software created by billion dollar corporations despite costing far less to develop. Rather than view it as competitive, the best, most forward-looking firms are beginning to embrace this model, wherein consumers and users of software become co-creators and participate in the value creation process:

[A]s a result of earlier consumer psychology studies that essentially pointed to the existence of the IKEA effect, many firms transitioned from viewing consumers as “recipients of value” to instead “co-creators of value.” One element of this shift was the involvement of consumers in product design, marketing, and testing. (Wikipedia)

In the not too distant future, choosing software to fill our digital spaces may feel a bit more like choosing furniture to fill our physical spaces. We’ll have the choice to use software that works out of the box, or software that’s labeled “some assembly required,” and we’ll all be better off for having this choice.

-

For instance, I would never have guessed that the time on my VM being off by just a few seconds would cause so many of my validator’s attestations to fail to post. I learned this the hard way and it was a valuable lesson! ↩