Crypto Has a Purpose Problem

Blockchain and cryptocurrency projects have struggled to articulate a clear, positive, inclusive mission statement. This may prove to be their Achilles heel.

Trying to arrive at a mission or a set of shared values in the crypto community often feels like this. A company, or project, is like a car: it can take us many places, but we must first figure out where it is that we want to go. Photo by Daniele Levis Pelusi on Unsplash

I recently read the excellent book The Infinite Game by Simon Sinek. The idea of the book is that every organization must choose between having a finite vision or an infinite vision (by “organization,” Sinek is referring not only to companies but also smaller scale initiatives such as projects as well as larger scale initiatives such as nation states). A finite vision is one that’s narrow, short-term, clearly defined and easily measured: for instance, to develop a certain product, to capture X% of the market share of an industry, or to achieve a billion dollar valuation. Because they’re attractive and clearly defined, most organizations are built around such finite visions.

An infinite vision, by contrast, is far broader in scope and far harder to measure. Organizations with an infinite vision care less about short-term vanity metrics like sales, market share, or valuation and more about intangibles like trust and quality of life. As a result, they’re willing to sacrifice some short-term gains in exchange for long-term success and sustainability. The main point of the book is that organizations with an infinite vision outperform those with a finite vision: the trust, admiration, and loyalty they engender on the part of their employees, customers, and investors ultimately causes them to build better products and stronger brands, and to reduce churn. This is true in times of plenty, but it’s especially true in difficult times when sacrifices are necessary. And while it’s always been true, it seems ever more true today as we collectively wake up to the perils of a modern form of capitalism that’s too focused on the short-term.

One of the things that an organization with an infinite vision requires, says Sinek, is a Just Cause:

“[W]hen there is a Just Cause, a reason to come to work that is bigger than any particular win, our days take on more meaning and feel more fulfilling. Feelings that carry on week after week, month after month, year after year. In an organization that is only driven by the finite, we may like our jobs some days, but we will likely never love our jobs. If we work for an organization with a Just Cause, we may like our jobs some days, but we will always love our jobs… A Just Cause inspires us to stay focused beyond the finite rewards and individual wins… [L]eaders who want us to join them in their infinite pursuit must offer us, in clear terms, an affirmative and tangible vision of the ideal future state they imagine.”

Reading Sinek’s description of a Just Cause made me reflect on the organizations I’ve been part of and projects I’ve contributed to throughout my life and my career. Like many of us, I’ve been part of organizations with a Just Cause, and of some without. The ones with a Just Cause tended to be non-profits, whereas the for-profit organizations I’ve contributed to tended to be focused on developing a particular product or maximizing sales, precisely the sort of short-sighted, finite vision that Sinek describes. And I’ve left at least two organizations because they lacked a Just Cause.

The first is the hedge fund that I worked for after college. While the managers and employees of the firm had their hearts in the right place, and while the firm did some good in the world, it felt like an afterthought rather than the primary, motivating purpose behind the organization.

The second is Ethereum. My reasons for joining the Ethereum Foundation and contributing to the project in 2017 were clear to me: Ethereum represented an operating system for building better human institutions. (I hadn’t worked out the wording at that time, but I had an inkling of this. I later fleshed out this vision more clearly.) As the scale and density of human civilization continues to grow, as globalization continues to cause more diverse groups to come into daily contact, and as the fast pace of technological change continues to exacerbate inequality, our institutions are more important than ever before. And while most of the institutions we rely on today are broken, a fact that’s become extremely obvious over the past few years, tools like smart contracts and cryptoeconomics offer a genuinely novel way to design and build future human institutions: ones that are fairer, more transparent and accountable, and more participatory.

That was my personal vision for Ethereum, but sadly it’s not a vision that was shared by most of the people I met in the Ethereum community. Many of my fellow core developers were attracted to Ethereum because of the technological complexity and challenge. While I respect and identify with this feeling, it’s not a Just Cause. Many others were attracted by the idea of self-sovereign money or uncensorable applications. I can identify with these goals, too, but they’re also not a Just Cause mainly because they’re a negative rather than a positive vision: opposition to state interference rather than a vision for something novel and constructive.

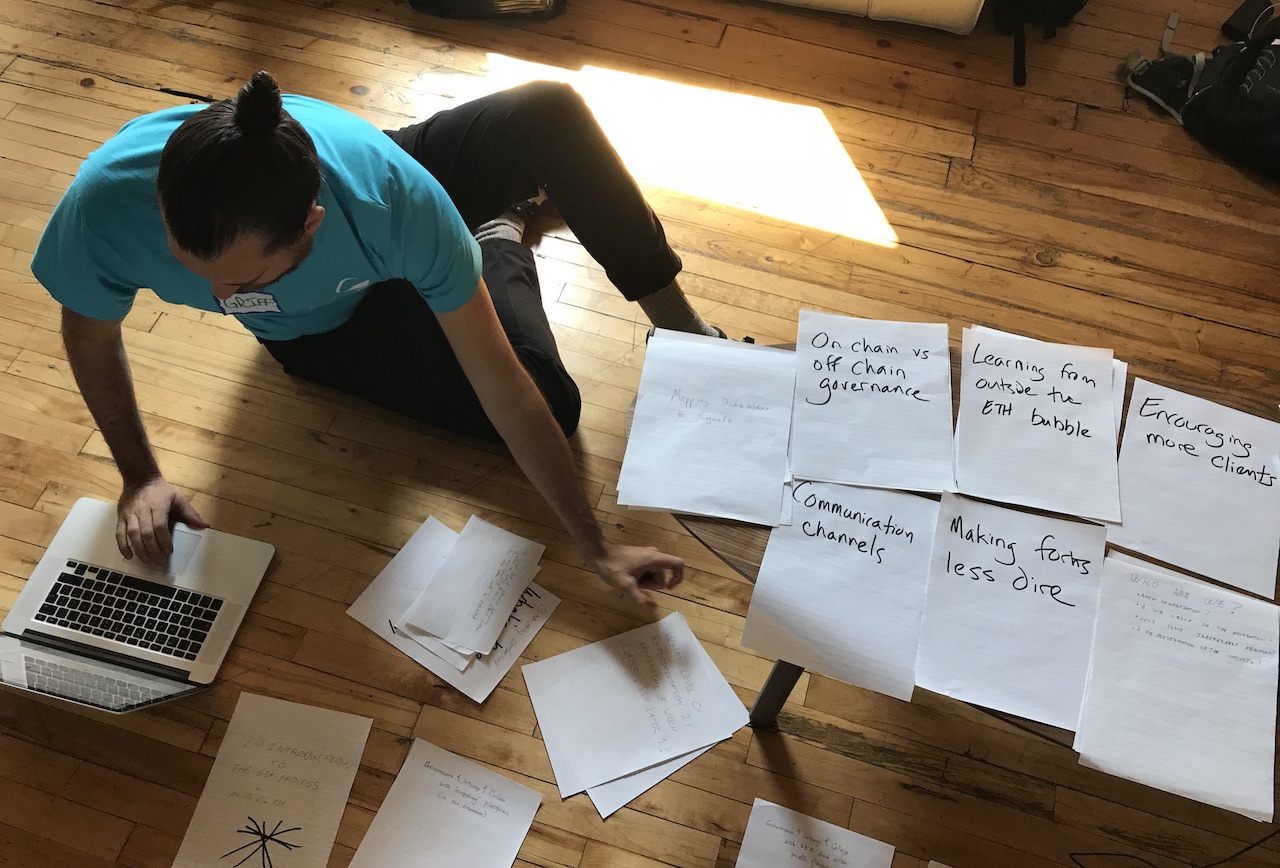

#EIP0, the Ethereum governance summit held in Toronto in 2018. Image by the author.

In April 2018, I helped convene a governance summit called #EIP0 with many other stakeholders from the Ethereum community. We discussed many interesting and challenging aspects of governance such as the EIP process and coordinating multiple independent full node implementations. One thing we got stuck on, however, was mission and values. We spent hours debating the topic, but we could not agree on even a basic statement of shared principles or values. No attempt had ever been made to do this before in Ethereum, to my knowledge, and by 2018 it already felt too late. There were already too many competing interests. Miners, for instance, wanted transaction fees to be as high as possible to maximize their revenue, whereas users and app developers wanted fees to be as low as possible to spur adoption and usage. We were unable to escape from the weeds. The best we could do was, “Keep adding blocks to the chain.” That’s about as uninspiring a Just Cause as I can imagine.

One possible response is that Ethereum is not, in fact, a singular organization. It’s something more akin to a marketplace: an ostensibly neutral, unopinionated platform where many people and organizations, each with their own principles and purpose, can meet and transact. Proponents of this perspective may feel that Ethereum does not need principles or a purpose of its own.

While this idea may be attractive to Bitcoiners, right libertarians, and those who desire an idealistic form of neutral “rule by algorithm”, it’s pretty clearly not true of Ethereum. Spend five minutes at any Ethereum event and you would not for a moment think that the attendees weren’t members of a values-aligned community. What’s more, I saw clearly that many, if not most, of my fellow contributors were there largely because they felt a strong sense of purpose in working on the project.

While many clearly feel this purpose and there are clearly values shared throughout the Ethereum community, no one has successfully articulated them or rallied the community around a Just Cause. It may already be too late. While the first generations of contributors felt a strong sense of purpose, that sense has become diluted as the community has grown in size and diversity, and as more and more money has flowed into it. As Microsoft, Uber, Wells Fargo and many other companies have demonstrated, culture is something that you have to get right from the beginning, and keep getting right, or you’ll pay the price for a very long time. A community united by a profit motive is extremely fragile and will be quick to abandon ship when times get tough or when another, more attractive opportunity presents itself.

Ethereum is not the only crypto community that has struggled to clearly define or articulate its mission. Many crypto projects seem to exist out of a combination of curiosity in the technical challenge and economic opportunism, with little or no thought given to animating purpose or Just Cause. They tend to be more about libertarianism and escaping from systems perceived to be broken than they are about a constructive, positive, inclusive vision for the future.

According to Sinek, a Just Cause needs to have five properties: it needs to be (1) for something, i.e., affirmative and optimistic (rather than defined in terms of opposition to something), which also means that it needs to be clearly defined; (2) inclusive, open for all to contribute. (3) service-oriented, i.e., for the benefit of others; (4) resilient, able to endure change; and (5) idealistic: big, bold, and ultimately unachievable.

I tried to find the mission, vision, or purpose statement of several high profile blockchain and cryptocurrency projects (and the organizations behind them) using web searches such as “<project name> mission statement.” Here are a few that I found, and my sense of how they score according to Sinek’s criteria. First, some counterexamples:

- Ethereum: While Ethereum itself is a decentralized community and project without any singular mission statement (as described above), the Ethereum Foundation has a mission statement: “to promote and support Ethereum platform and base layer research, development and education to bring decentralized protocols and tools to the world that empower developers to produce next generation decentralized applications (dapps).” (source). Here’s another: “Our mission is to do what is best for Ethereum’s long-term success” (source). This sort of self-referential mission statement isn’t very helpful or meaningful. It’s egoistic and not resilient. It’s not service-oriented, not terribly inclusive, and not idealistic enough.

- Polkadot: Similar to Ethereum, Polkadot itself does not appear to have an official mission statement, but the mission statement of the Web3 Foundation, which is behind its development, is: “to nurture cutting-edge applications for decentralized web software protocols. Our passion is delivering Web 3.0, a decentralized and fair internet where users control their own data, identity and destiny. Polkadot is our flagship project.” (source) While it’s affirmative and idealistic, this mission statement does not seem terribly inclusive (it sounds like it appeals primarily to application developers), service-oriented (how does this serve humanity?), or resilient (what if Web 3 proves not to be what the world needs?).

- DFINITY: “DFINITY reinvents the public internet as a global computer hosting open internet services.” (source) It’s not clear if this is really the mission statement, but it’s all I could find. It’s vague, ill-defined, and doesn’t really check any of the boxes.

- Algorand (Algorand Foundation): “The Algorand Foundation’s mission is to promote the long-term success of the public blockchain network and the Algo token.” (source) This mission statement, similar to that of the Ethereum Foundation, is narrow, egoistic and self-serving. It says nothing about inclusivity or service to others, and doesn’t appear resilient or particularly idealistic.

And some positive examples:

- NEAR protocol: “to enable community-driven innovation to benefit people around the world. NEAR’s platform provides decentralized storage and compute that is secure enough to manage high value assets like money or identity and performant enough to make them useful for everyday people, putting the power of the Open Web in their hands.” (source) This is a pretty good mission statement. My only criticism is that it’s not specific enough: what, exactly, is meant by “community-driven innovation”, how does it benefit “people around the world”, and how does NEAR protocol enable it?

- Celo: “to enable prosperity for everyone” (source). This one is also pretty good, but also a little too vague and nonspecific. What is meant by “prosperity for everyone” and how does Celo uniquely enable this?

- Cosmos (Interchain Foundation): “to research, develop, and promote open, decentralized, network technologies like Cosmos, that provide greater sovereignty, security, and sustainability to the world’s communities. Our Vision: We believe that open-source, cryptographic, consensus-driven, economic networks hold the key to an anti-fragile global economic system and equal opportunity for all.” (source) This mission statement is also pretty good. Like those of NEAR and Celo, it’s also a bit vague. The vision of an “anti-fragile global economic system and equal opportunity for all” is compelling, but how and why do “network technologies like Cosmos” uniquely enable this?

- Blockstack: “to enable an open, decentralized internet which will benefit all internet users by giving them more control over information and computation.” (source) While this mission statement is positive, idealistic, and service-oriented, it’s also the vaguest of all these mission statements. How does giving users “more control over information and computation” benefit all internet users? How do ordinary people, such as internet users, contribute to this mission?

As the above sample mission statements show, some crypto projects and communities are far more mission-driven and purpose-oriented than others. Of course, putting words on paper is one thing, whereas living them and putting them into practice every day is something else entirely. Official mission statements are just one factor, albeit one that tends to be representative of a team’s and project’s overall priorities and culture. It would be an interesting exercise to look into how well each of these communities puts its stated mission and vision into practice.

As I wrote earlier in Constitution, people choose to contribute to projects for a variety of reasons, some intrinsic and some extrinsic. Those who contribute to a project because they feel a strong sense of mission, purpose, and/or values-alignment, are its missionaries. These are the types who will make sacrifices (such as working long hours or forgoing higher paying work elsewhere). They often feel a strong sense of duty or loyalty and will stick around even when times are tough. On the other hand, those who contribute on a more transactional basis are a project’s mercenaries. They may also make valuable contributions, but they’ll be much more likely to go elsewhere when things get tough or when they get a better offer elsewhere.

I hypothesize that, just like the firms Sinek examines in The Infinite Game, blockchain and cryptocurrency projects that are better able to clearly articulate a Just Cause that meets the above criteria, and to truly put that cause into practice, will do a better job of attracting and retaining talented contributors. As those contributors will consist largely of missionaries (as opposed to mercenaries), mission-driven projects will have to pay them less and they will be more likely to stick around even through difficult times.

In fact, a Just Cause and a project’s culture more generally has appeal beyond just the core team. Customers and users tend to be more loyal towards firms and projects with which they feel a sense of alignment in values and purpose, and they are more likely to act as advocates on the behalf of such a project. For the same reason that crypto projects without a positive, clear, inclusive, resilient, service-oriented, idealistic mission will have trouble attracting and retaining talented contributors, they will also struggle to attract and retain users, especially in the face of greater and more diverse competition. Bitcoin and Ethereum have a clear head start, but the fact that neither has a clear mission or Just Cause may prove to be an Achilles heel over time.

In closing, while projects like Bitcoin and Ethereum were founded with a set of libertarian, anti-establishment values, those values do not quite constitute a Just Cause, and they’ve anyway become diluted over time. Blockchain and cryptocurrency have generated an enormous amount of wealth for a small group of people, but that wealth has by and large been generated not because of values-aligned communities executing on clear, inclusive, service-oriented missions, but rather in spite of not having such missions. As a result, unless and until these projects and their constituent communities are better able to articular a clearer Just Cause, this wealth generation process may not be sustainable. As Sinek wrote,

“Money is the fuel to advance a Cause, it is not a Cause itself. The reason to grow is so that we have more fuel to advance the Cause. Just as we don’t buy a car simply so we can buy more gas, so too must companies offer more value than their ability to make money. A company, like a car, is more valuable to all constituents when it takes us somewhere to which we would otherwise be unable to go. That place we envision going to is the Just Cause.”

A blockchain is not a company, but cryptocurrency represents a powerful new form of money, a novel sort of fuel that can take us quite far. The question is, where do we want it to take us?